Pelvic Congestion Syndrome involves dilated ovarian veins (“congested” ovarian vein on right) leading to varicose veins around the uterus and ovaries. PCS – also known as pelvic venous insufficiency – is a chronic condition where varicose veins form in the pelvis, causing blood to pool and pressure to build up. This typically results in a constant dull ache in the lower abdomen and other disruptive symptoms. PCS predominantly affects women of childbearing age (20 to 45 years) and is uncommon after menopause.

It is a major under-diagnosed cause of chronic pelvic pain – research suggests it may account for up to 30% of chronic pelvic pain cases. In other words, many women suffering pelvic pain for years might actually have PCS without knowing it.

In Singapore and worldwide, awareness of PCS is growing. Our goal is to explain the key aspects of this condition in a clear, comprehensive manner. In the first part of our deep delve, we will cover what causes PCS, its symptoms, and how doctors diagnose it. In the second part of our series, we will look into the advanced treatment options that can provide lasting relief. We also discuss recovery, when to seek help, local insurance considerations, and answer frequently asked questions.

Causes and Risk Factors

PCS essentially arises from poor blood flow in the pelvic veins. In healthy veins, tiny one-way valves keep blood flowing upward toward the heart. In PCS, these valves become weakened or damaged, allowing blood to flow backward (venous reflux) and pool in the pelvis. The ovarian veins and uterine vein plexus often become enlarged and twisted – similar to varicose veins in the legs, but hidden deep in the pelvis. Several factors can contribute to this problem:

- Pregnancy-related changes: Pregnancy is a leading factor. During pregnancy, blood volume increases and veins must expand (up to 50% wider) to handle the flow. High estrogen and progesterone levels relax vessel walls. These normal changes can stretch veins and permanently damage valves. Women who have had multiple pregnancies are at higher risk, as repeated stretching leaves pelvic veins dilated even after delivery. This is why PCS is more common in women with two or more children.

- Hormonal influences: The female hormone estrogen can weaken vein walls. PCS is rare after menopause, suggesting estrogen during reproductive years plays a role. Conditions or treatments that increase estrogen (e.g. multiple IVF cycles or certain hormonal medications) might predispose a woman to PCS.

- Venous compression syndromes: In some women, an anatomical vein compression triggers PCS. Two key examples are May-Thurner syndrome and Nutcracker syndrome. In May-Thurner syndrome (MTS), the left iliac vein (which drains the left leg and pelvis) is compressed by the overlying right iliac artery, impeding blood outflow. In Nutcracker syndrome (NCS), the left renal vein (which the left ovarian vein drains into) is compressed between arteries (the aorta and superior mesenteric artery). These compressions create high back-pressure in pelvic veins, leading to varicosities and congestion upstream. Women with these conditions can develop PCS symptoms even without pregnancies or hormonal factors.

- Genetic and other factors: A family history of varicose veins or inherently weak connective tissue may increase risk. Some women are simply more prone to vein valve failure. Also, having leg varicose veins at a young age or visible vulvar varicosities can correlate with higher PCS risk. Often, multiple factors overlap – for instance, a woman with a mild vein compression who then undergoes pregnancies may experience a “perfect storm” leading to PCS. It’s worth noting that other pelvic conditions (like endometriosis or fibroids) can coexist with PCS and sometimes confuse the picture, although they do not cause PCS.

Common Symptoms of PCS

Chronic pelvic pain is the hallmark of pelvic congestion syndrome. This pain is typically a persistent, dull ache deep in the pelvis lasting >6 months, not limited to menstrual cramps. Key characteristics of PCS pain include:

- Worse when standing or late in the day: Prolonged standing or sitting makes the pain intensify (gravity causes blood to pool). Many women feel increased pelvic heaviness by day’s end, with relief when lying down.

- Pain during or after intercourse: PCS often causes dyspareunia (pain with sexual intercourse) and a lingering ache for hours afterward due to engorged pelvic veins. Post-coital pelvic pain is a red flag for PCS.

- Menstrual cycle effects: While PCS pain isn’t directly caused by menstruation, many patients report their pelvic pain flares premenstrually or during menses. Hormonal changes that occur around the period can further dilate veins, exacerbating the congestion.

- Radiating pain to back or legs: The dull pelvic ache can radiate to the lower back, hips, or thighs, sometimes mimicking back pain or sciatica. A heavy, dragging sensation in the legs may accompany it in some cases.

- Feeling of fullness or pressure: Many women describe a feeling of pelvic fullness or pressure. There may be a sense of bloating in the lower abdomen.

Beyond pain, PCS can produce other signs and symptoms that are often overlooked or attributed to other issues:

- Visible varicose veins in unusual areas: Varicose veins may appear on the buttocks, upper thighs, vulva, or around the genital area. These are important clues – varicosities in such locations strongly suggest internal pelvic vein congestion as the source of the problem. For example, some women with PCS develop prominent vulvar varicose veins, especially during or after pregnancy.

- Urinary or bowel symptoms: The engorged pelvic veins can press on nearby organs. Women might experience bladder irritability (frequent or urgent urination) or even mild stress incontinence (leakage when coughing). Irritable bowel symptoms (alternating diarrhea or constipation) can occur in some cases due to vein engorgement near the bowel. These symptoms are not specific to PCS but, when combined with pelvic pain, they support the diagnosis.

- Pelvic tenderness: On physical exam by a gynecologist, there may be tenderness when pressure is applied over the ovaries or along the pelvic side walls/floor. This tenderness, together with the above symptoms (pain pattern, varicosities), raises suspicion for PCS.

- Emotional impact: Living with unrelenting pelvic pain can take an emotional toll. Many women with PCS report fatigue, mood changes, anxiety or depression as a result of their chronic pain and its effect on daily life. It’s important to acknowledge and address this—chronic pain is very real and can affect mental well-being.

Bottom line: If you have pelvic pain that worsens with standing or after sex and isn’t explained by other gynecological issues, PCS could be the culprit. Recognizing the symptom pattern is the first step toward getting proper help.

How Pelvic Congestion Syndrome is Diagnosed

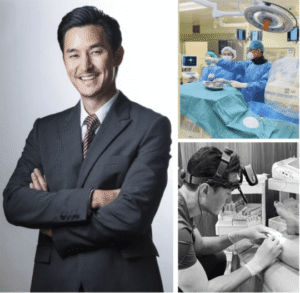

Diagnosing PCS can be challenging because its symptoms overlap with many other conditions (endometriosis, uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts, etc.). In Singapore, patients often first consult an OBGYN for chronic pelvic pain. If initial gynae evaluations are inconclusive, it’s important to consider a vascular cause. Dr. Darryl Lim takes a comprehensive approach, usually in collaboration with a gynecologist. The typical diagnostic process includes:

- Detailed Medical History: Dr. Lim will discuss your pain characteristics in depth – when it started, how it varies, and what worsens or relieves it. Certain clues tip off a venous issue: for example, if pain improves when lying down or worsens after long periods standing, PCS is suspected. Your obstetric history (number of pregnancies), menstrual cycle patterns, and any prior pelvic diagnoses or surgeries are also reviewed. This history helps distinguish PCS from other causes of pelvic pain.

- Physical Examination: A gentle pelvic exam is performed to check for any tenderness or pelvic organ enlargement. Tenderness along the ovarian vein path (deep in the left/right lower abdomen) can suggest PCS. The exam also looks for any visible varicose veins on the buttocks, thighs or vulva – finding those greatly strengthens the case for a pelvic venous disorder.

- Pelvic Ultrasound Scan (Doppler): An ultrasound scan is usually the first-line imaging test for PCS. This may include a transvaginal ultrasound for a closer look at pelvic structures. With Doppler ultrasound, the sonographer can visualize blood flow in the ovarian veins and pelvic region. Ultrasound can often show dilated ovarian veins or slowed/reversed flow indicative of reflux. It’s a non-invasive, radiation-free test that is widely available. However, in some women the pelvic veins can be hard to see by ultrasound (depending on anatomy or bowel gas), so further imaging with other modalities might be needed.

- Advanced Imaging (CT or MRI): If ultrasound is inconclusive or more detail is required, a CT scan or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis is usually performed. These provide a detailed map of the pelvic blood vessels and can confirm enlarged ovarian veins or pelvic varices that ultrasound might miss. MRI is particularly useful as it can simultaneously check for other pelvic pathology (like endometriosis or fibroids) to ensure nothing is overlooked. Also, CT/MRI can also detect the anatomical compression syndromes (May-Thurner or Nutcracker) if present. For example, an MRI might show a compressed left renal vein or iliac vein, alerting the doctor that stenting could be needed as part of treatment.

- Diagnostic Venography: The gold standard for confirming PCS is an ovarian venogram – an X-ray of the pelvic veins using contrast dye. This is an invasive test, typically done by an interventionist in a catheterization lab. Under local anesthesia, a thin catheter is inserted (usually via a vein in the groin or neck) and guided to the ovarian veins. Contrast dye is injected to make the veins visible on X-ray. Venography can directly show refluxing blood and engarled pelvic veins, providing definitive diagnosis. The advantage is that if significant varices are seen, treatment (embolization) can be done in the same session, sparing the need for a subsequent extra procedure. In practice, venography is often reserved for when non-invasive tests strongly suggest PCS and the plan is to proceed with an intervention.

Throughout the evaluation, the team will exclude other causes of pelvic pain (differential diagnosis). Common conditions like endometriosis, adenomyosis, uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts, interstitial cystitis, or pelvic floor muscle pain can cause similar symptoms. Indeed, many patients with PCS have undergone gynecologic workups or treatments for these conditions first. A thorough workup ensures “no stone is left unturned” – often meaning collaboration between your gynecologist and a vascular specialist. Only by ruling out or treating other issues can we confidently pinpoint PCS as the true cause of pain and target it appropriately.

Need Expert Vascular Care?

Book an appointment with Dr. Darryl Lim today and get a personalized treatment plan for your vascular health.

Conclusion

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome is a complex condition that often hides in plain sight- mistaken for more familiar gynaecological problems or simply dismissed as “part of being a woman”. But understanding the underlying causes, recognising the distinctive pattern of symptoms, and knowing what to expect from a diagnostic workup can make all the difference. With growing awareness and advances in imaging, more women in Singapore are finally getting answers.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll explore how PCS is treated- ranging from minimally invasive embolisation to supportive therapies, and what recovery looks like. If the symptoms described here resonate with you or someone you know, don’t hesitate to seek a proper evaluation with Dr. Darryl Lim. With the right care, you can take the first step toward a pain-free life.

Frequently Asked Questions about Pelvic Congestion Syndrome (PCS) Symptoms and Diagnosis

Q: What is pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS)?

A: It’s a medical condition where veins in the pelvis (around the ovaries and uterus) become enlarged and congested with blood due to faulty valves. This venous congestion causes chronic pelvic pain and varicose veins in the pelvic region. Essentially, PCS is like “varicose veins of the pelvis” leading to ongoing ache and pressure.

Q: What are the symptoms of PCS?

A: The main symptom is a dull, aching pelvic pain lasting >6 months. The pain typically worsens as the day goes on or after long periods of standing, and improves when lying down. Pain during or after sex is common, as is a heavy or dragging feeling in the pelvis. Other signs include visible varicose veins on the buttocks, thighs or vulva, and sometimes increased urinary frequency or bowel discomfort due to pressure on nearby organs. Many women also experience lower back pain or leg aches in conjunction with the pelvic pain.

Q: Who is at risk of developing PCS?

A: PCS mainly affects women of reproductive age (20s to 40s), especially those who have had multiple pregnancies. Pregnancy is a big risk factor because it stretches the pelvic veins and can damage their valves. Women with a history of varicose veins (for example, in the legs or vulvar area) are at higher risk, as are those with family history of vein problems. Pre-menopausal women are far more likely to have PCS than post-menopausal (estrogen seems to play a role). Additionally, if someone has an underlying condition like May-Thurner or Nutcracker syndrome, that can predispose them to PCS even if they never had children.

Q: How is PCS diagnosed?

A: Diagnosis usually starts with a clinical evaluation – the doctor will consider the symptom pattern and do a pelvic exam. Non-invasive imaging like a pelvic ultrasound with Doppler is typically the first step. If that suggests PCS or is inconclusive, an MRI or CT scan can provide more detail on pelvic veins and check for any vein compressions. The definitive confirmation is done by pelvic venography – an X-ray with contrast dye to directly visualize the ovarian veins – which is often combined with treatment in the same sitting. Do note that it is important to exclude other causes of pelvic pain (like endometriosis, fibroids, etc.) during the workup.